The Day I Saw Bix's Hankie

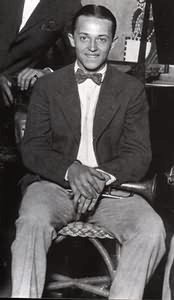

Herewith an article I wrote for the fondly remembered Scat Magazine a little while back. RE: the photo, no it is not a Radio Bow Tie.

Hanky Panky

With stages arrayed around the grounds of the Old U.S. Mint, the first weekend in August is the busiest of the year for the Louisiana State Museum’s Jazz Collection. Ever since the first Satchmo Summerfest in 2001, great throngs of visitors assemble on lower Esplanade each year to pay homage to Louis Armstrong.

The Jazz Collection, still known affectionately to many as the Jazz Museum (apropos of its roots as an extension of the New Orleans Jazz Club), is best known for its assortment of musical instruments used by famous and not so famous jazz musicians. All told there have been more than 150 donated over the years. They form the centerpiece of the state’s collection, housed on the second floor of the Mint. It’s the largest collection of its kind and includes the trombone Kid Ory played to accompany a young Armstrong on the legendary Hot Five recordings, Sidney Bechet’s saxophone, and Dizzy Gillespie’s trumpet with its oddly angled bell. There are also the instruments of lesser known figures—an intensely filligreed trumpet used by Oscar “Papa” Celestin for example, or a guitar from Dr. Edmond Souchon.

A display of instruments is the first thing visitors encounter in the dim light of the collection’s entrance, making up a sort of ghostly tableau. Six instruments silent behind the plexiglass, a band on permanent break.

Moving through the exhibits, Steven Teeter, a Jazz curator at the Museum, puts names to the trumpets and trombones, clarinets and saxophones. He points out Pete Fountain’s first horn and Alcide “Slow-Drag” Pavageau’s home-made bass. And then there is the instrument for which the collection is best known, Armstrong’s first cornet from his days at the Milne Boys Home. In many ways, the instruments of famous musicians make for an odd display. It’s like looking at a collection of Picasso’s paintbrushes or Rodin’s tools. The art of George Lewis, for instance, wasn’t the clarinet itself, but the ethereal sounds it produced.

But the Collection is also home to odd personal effects; photos and letters and business cards, which have a particular appeal. In a Proustian way, these objects conjure the everyday lives of jazzmen, not just the music they created. Like Bix Beiderbecke’s handkerchief.

“Here it is,” says Teeter, as he takes a grey archival storage box from a shelf across from the desk in his office. He opens the box to reveal a large swatch of thin woven cloth printed with an art deco design and edged with tan piping. Much care seems to have been taken to preserve what looks like a fairly ordinary, if old and faded, gentleman’s hanky. But when one thinks that it wiped the brow of the cornetist whose tone was famously described as “like a girl saying yes,” it becomes extraordinary.

To look at Bix’s handkerchief is to remember, in an instant, a story of genius and tragedy. As a youngster in Davenport, Iowa, he came under the spell of recordings by Nick LaRocca and the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. He made historic recordings with the Wolverines and the orchestras of Jean Goldkette and Paul Whiteman—all before age 28, when he died, a symbol of roaring twenties excess.

The handkerchief, which has not yet been put on display at the Mint, has a history, too, beyond Bix’s demise. In 1963, Hoagy Carmichael—composer of “Star Dust,” “Georgia on my Mind,” and the lesser known and brooding “New Orleans”—donated it to the museum, along with a pair of cufflinks. In the accompanying letter, Carmichael details how he got the items from a “Miss Weiss” shortly after Biederbecke’s death. The cufflinks, he says, were the ones “he was wearing just before his last illness.” In fact, among the many bad habits Beiderbecke was known for were his sartorial ones. Stories abound of ill-fitting rumpled tuxedoes. So it is no surprise that the cufflinks, both done up in highly ornate black and gold, are mismatched.

The cufflinks, the letter, with its post script suggesting the handkerchief not be laundered, and one of Bix’s old cornets, share a case in the back of the jazz wing of the museum. A number of other items associated with Beiderbecke are on also on display. There is a piano, a Wurlitzer console that Bix played while living in a hotel on 44th Street in New York, above it a copy of the sheet music to his composition “In a Mist” and several photographs. One photograph in particular, taken while Bix was in the Jean Goldkette Orchestra, catches Teeter’s fancy. Like the handkerchief, the handwritten inscription Bix left behind gives us something of the young man who revolutionized music. Teeter leans over to read what Bix wrote: “ ‘To Les, personnally’ and here Bix corrects himself, he writes above the word ‘only one ‘n’—‘and musically I think you’re the nuts and that’s no east of Buffalo stuff.’ ”

—Jon Pult

3 Comments:

Awesome post. Thanks!

Completely I share your opinion. In it something is and it is good idea. It is ready to support you.

I apologise, but, in my opinion, you are not right. Let's discuss it. Write to me in PM, we will communicate.

Post a Comment

<< Home